on

By Jacqueline Holness

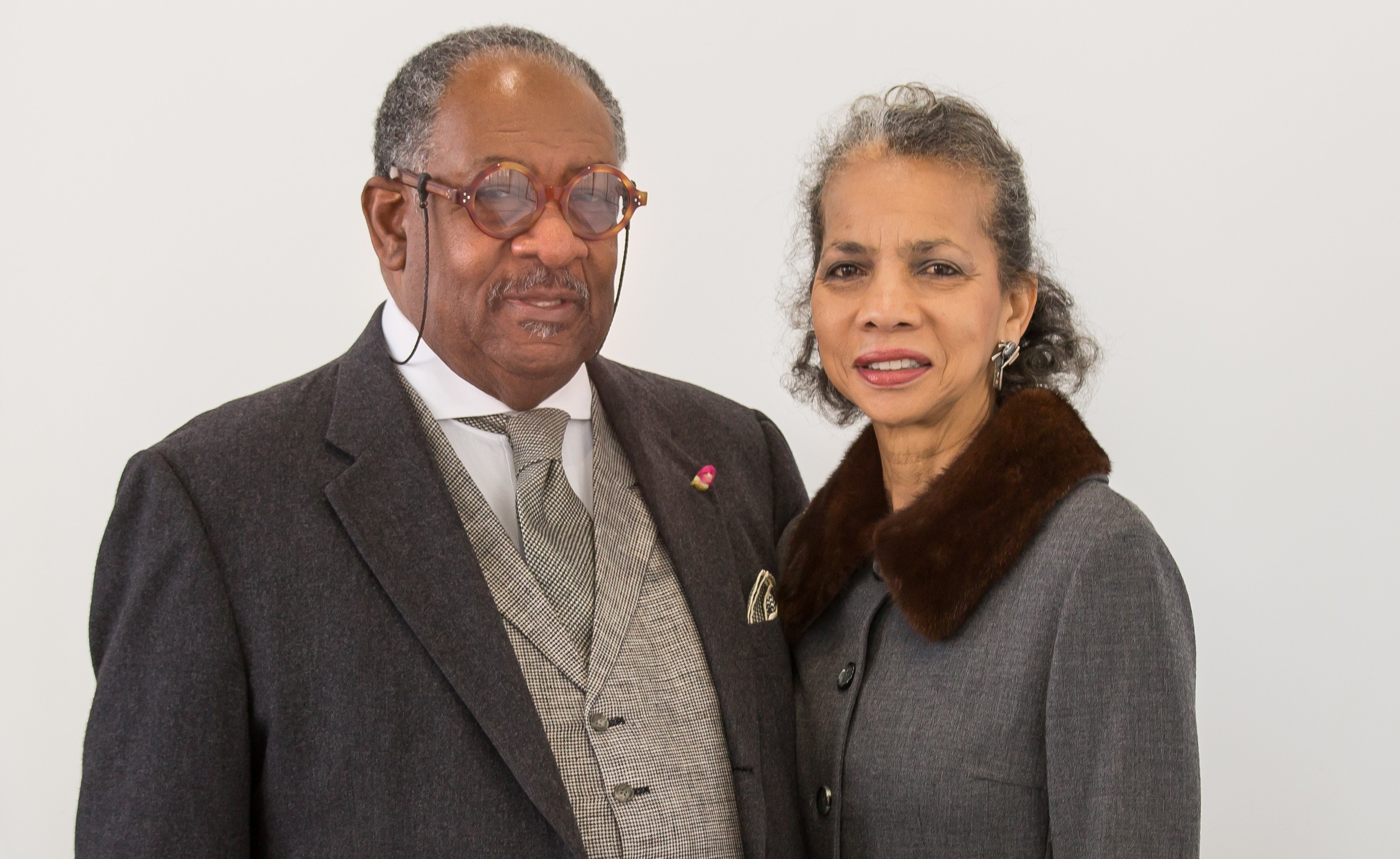

It would seem by design that William J. Stanley III, the first black graduate of Georgia Institute of Technology’s College of Architecture, and Ivenue Love-Stanley, who would become the first black woman to graduate from the College of Architecture at Georgia Tech, met on his last day and her first day on campus in 1972. But it was a coincidence. After her parents dropped her off, Ivenue ventured to what was called the “Black House,” which was on 10th Street, to meet other black students who congregated there. “I walked up and I saw this guy who had hair to here,” says Ivenue, pointing to her shoulders. “He had a cigarette in one hand and a bottle of Boone’s Farm in the other hand. He was loading a mattress onto his piece of a car.” “No, it was a convertible Karmann Ghia,” says William, with laughter, picking up the story. Having loaned his furniture to the “Black House,” William was recovering from a party the night before. “It was called an O.B. Fly party which stands for Old Babes From Last Year. If you were an upperclassman, we gave you a party before the freshmen arrived the next day. It was the last summer party.”

After they exchanged names and Ivenue told him she would be studying architecture, William said, “Well, study me, I’m an architect.” That afternoon, the Atlanta native showed the city’s architecture to the Meridian, Miss., transplant. “I gave her the grand tour — the High Museum, out in Buckhead, in Collier Heights, everywhere.” As Stanley, Love-Stanley, the architectural firm the couple founded in 1978, William and Ivenue have added to the sights of Atlanta’s skyline the two toured years earlier. Reynolds Cottage at Spelman College, John Hope Hall Science Research Facility at Morehouse College, Lyke House – The Catholic Center at Atlanta University Center, Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church, Herndon Tower at the First Congregational Church UCC, the Olympic Aquatic Center at the Georgia Institute of Technology; Horizon Sanctuary and Martin Luther King Sr. Resource Center at Ebenezer Baptist Church are just a sampling of their noteworthy Atlanta projects the firm has completed as the second largest African-American architectural practice in the South. But the first project of the couple, who married in 1978, was their first home. “The house was raggedy and really a wreck,” says William. “But we started working on the house, designing it, taking it apart, putting it back together, learning lessons about actual construction.” “The house was featured in Homes of Color magazine in 2003,” says Ivenue. “We were working together from day one,” William adds. While they work together, they bring different skills to their business. William takes the lead on design while Ivenue takes the lead on production, which matches their personalities. “She’s straight-laced and prim and proper, and I’m a bon vivant,” says William. “He’s Paris, and I’m Berlin,” Ivenue says. In fact, their different approaches led to her parents questioning her before they married. “They asked are you sure you want to marry and work together because it’s a lot of time together, but it has worked.” Their pairing has resulted in numerous awards and accolades. The American Institute of Architects bestowed the 2014 Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award upon Ivenue and named William the 52nd chancellor of the College of Fellows of the organization also in 2014.Although working on the Olympic Aquatic Center, a joint venture with Smallwood, Reynolds, Stewart, Stewart and Associates at their alma mater has been a highlight, the collapse of a steel beam at the center was a low point for the firm. “It was big news,” says William of the 1996 Summer Olympics venue. “The construction method used for it was the cause, but it was our joint venture. It was under our seal.”

After they exchanged names and Ivenue told him she would be studying architecture, William said, “Well, study me, I’m an architect.” That afternoon, the Atlanta native showed the city’s architecture to the Meridian, Miss., transplant. “I gave her the grand tour — the High Museum, out in Buckhead, in Collier Heights, everywhere.” As Stanley, Love-Stanley, the architectural firm the couple founded in 1978, William and Ivenue have added to the sights of Atlanta’s skyline the two toured years earlier. Reynolds Cottage at Spelman College, John Hope Hall Science Research Facility at Morehouse College, Lyke House – The Catholic Center at Atlanta University Center, Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church, Herndon Tower at the First Congregational Church UCC, the Olympic Aquatic Center at the Georgia Institute of Technology; Horizon Sanctuary and Martin Luther King Sr. Resource Center at Ebenezer Baptist Church are just a sampling of their noteworthy Atlanta projects the firm has completed as the second largest African-American architectural practice in the South. But the first project of the couple, who married in 1978, was their first home. “The house was raggedy and really a wreck,” says William. “But we started working on the house, designing it, taking it apart, putting it back together, learning lessons about actual construction.” “The house was featured in Homes of Color magazine in 2003,” says Ivenue. “We were working together from day one,” William adds. While they work together, they bring different skills to their business. William takes the lead on design while Ivenue takes the lead on production, which matches their personalities. “She’s straight-laced and prim and proper, and I’m a bon vivant,” says William. “He’s Paris, and I’m Berlin,” Ivenue says. In fact, their different approaches led to her parents questioning her before they married. “They asked are you sure you want to marry and work together because it’s a lot of time together, but it has worked.” Their pairing has resulted in numerous awards and accolades. The American Institute of Architects bestowed the 2014 Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award upon Ivenue and named William the 52nd chancellor of the College of Fellows of the organization also in 2014.Although working on the Olympic Aquatic Center, a joint venture with Smallwood, Reynolds, Stewart, Stewart and Associates at their alma mater has been a highlight, the collapse of a steel beam at the center was a low point for the firm. “It was big news,” says William of the 1996 Summer Olympics venue. “The construction method used for it was the cause, but it was our joint venture. It was under our seal.”

Ivenue was disappointed by the responses of others. “You think about encouragement, when it happened, I’m sure there are jealousies, but no one came up and said to us, ‘Are you okay?’ It was traumatic.” Many of their projects have been for religious organizations. “My cousin in Chicago, who is an architect, told me, ‘Don’t work for those preachers. They don’t pay.’ He did a lot of ecclesiastical buildings,” says William. “So, for a long time, I didn’t seek them out. But if you get a good client, it’s fine.” Designed to resemble an African hut and featuring African-style crosses with other Afrocentric details, the Horizon Sanctuary at Ebenezer Baptist Church has likely become one of the firm’s most famous edifices, and William enjoys visiting the church. “Seeing the dancers perform, the choir jumping up and down, the preacher, folks moving up and down the aisle, the drums beating, the symphony performing. You derive great joy seeing people enjoy what you have designed. That is what it’s all about.

Join our email list to stay connected.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login